The Progress and Setbacks of Affirmative Action for Women’s Political Representation

After 25 years of reform, the struggle for women's political representation is still full of problems. Although the constitution and regulations have progressed. But technical regulations and implementation are increasingly moving away from legal instruments and guidelines.

The General Elections Commission of Indonesia [Komisi Pemilihan Umum Republik Indonesia or KPU RI] member for the 2012-2017 period, Ida Budhiati repeated that the guidelines for election management are the constitution. The highest guidelines in administering the state, both in responding to, guaranteeing, and protecting the constitutional rights of its citizens. The constitution even clearly stipulates affirmative action for women's political representation as Article 28H Paragraph (2) of the amendment to the 1945 Constitution which emphasizes “Every person has the right to receive ease and special treatment to obtain the same opportunity and benefit in order to achieve equality and fairness.”

"This is a collective awareness that the Indonesian people, especially women, experience discrimination, are left behind in the political field so that tools and special treatment are needed to achieve equality and justice," said Ida in a public discussion entitled "25 Years of Reform: Quo Vadis Women's Political Representation? ” (6/20).

The implementation of Article 28 H Paragraph (2) then underlies the use of the zipper system as an effort to encourage women to obtain top positions on the list. But in practice, the application of the zipper system deviates from the constitution. “The certainty provided by the constitution and laws has now become faint and barely audible. This is a setback in regulation for the 2024 election,” explained Ida.

Not to mention, said Ida, the method of calculating 30% by rounding it down has the potential to reduce the number of women candidates. Another setback is the way of placing women are no longer simulated in the PKPU (General Elections Commission Regulation). Accordingly, the technical elements in PKPU regarding the candidacy information system also complicate parties that wish to place women in the top positions on the list. “This situation certainly does not contribute to increase representation,” she said.

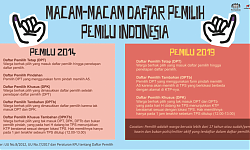

In terms of regulations, Bawaslu [Election Supervisory Body] member for the 2008-2012 period, Wahidah Suaib explained that after the reform there were three regulations related to women's political representation. First, Law Number 22 of 2007 on the General Election Organizers. This is the first law that regulates the representation of women in the membership composition of the KPU and Bawaslu. However, it has not regulated the 30% representation in the composition of the membership of election organizers selection team. "We see that in Article 12 and Article 87 which regulate the appointment of the KPU and Bawaslu, there is no regulation regarding the representation of women in the selection team," explained Wahidah.

The second regulation is Law Number 15 of 2011 concerning General Election Organizers. Article 12 concerning the KPU selection team and Article 86 concerning the Bawaslu selection team have also accommodated women's representation. "It has been written there that the President forms a selection team of 11 people by taking into account the representation of women, but there is no word of 30% yet," said Wahidah. Another drawback is that the regulation only regulates the selection team at the central level. This, continued Wahidah, is a consideration for the General Election Commission [KPU] and the Election Supervisory Body [Bawaslu] to cover their gaps through PKPU and the Bawaslu Regulations, which regulate 30% representation of women in the composition of the selection team.

Third, regulatory progress can be seen in Law Number 7 of 2017 on General Elections. In terms of appointing KPU and Bawaslu members, Article 22 paragraph (1) and Article 118 emphasize that the composition of the selection team needs to pay attention to the representation of women at least 30%. Another progress, said Wahidah, is the technical regulation of Bawaslu referring to the affirmation article on increasing women's representation.

“In the registration stage, if 30% of women registrants are not reached, the registration will be extended for 3 days. In the event that this is achieved, for example, the number of applicants meets the requirements for registration but has not reached 30% women, then the registration will be extended specifically for women.”

Wahidah added that another technical article prioritizes affirmations to include women if there are equal numbers of candidates.

Although the regulation encourages women’s representation to strengthen, it is the opposite in implementation. The gap in the composition of members of the election organizers can even be seen at the central level. According to Wahidah, the composition of 30% women membership in both the KPU and Bawaslu was only achieved in the 2008-2012 Bawaslu period and the 2007-2012 KPU period. “After that, there was only one woman who became a commissioner at both the KPU and the Bawaslu. This is clearly a setback,” explained Wahidah.

Chair of Kaukus Perempuan Parlemen [the Parliamentary Women's Caucus], Diah Pitaloka stated that the important thing that can be done is to promote affirmative action as a narrative. This alignment effort is aimed at making affirmative action continue to be discussed in the context of Indonesian democracy.

"So, people today talk about elections, talk about presidential candidates, talk about legislative elections, yes, they are very competitive, but democratic values like we talk about emancipation, we talk about discrimination, we talk about affirmation, democratic values which are of a substance are rarely discussed in election," Diah said

Diah believes that affirmative action narratives need to be passed on to the new generation. This is because the new generation has diverse values, perspectives, and concerns on issues. "So then how do we transform the narrative of affirmative action, the narrative of emancipation, in today's political context," said Diah.

Development of affirmative action narratives needs to be pursued so that cross-generations do not lose meaning. Even in practice, this is a step to continue to build a joint strategy, especially for Indonesian women who are ready to contest and to support fellow women in the political sphere.

Diah believes that discussing democratic values, such as discussing emancipation strategies, is a way out of the populist trap of democracy. This step is a way to ward off the attitude of the people who are indecisive and even apathetic towards elections.

The progress and setbacks of affirmative action for women's political representation, according to the Executive Director of Pusat Kajian Ilmu Politik Universitas Indonesia [the Center for Political Studies at the University of Indonesia] (Puskapol UI), Hurriyah, can easily be identified. They are, among others, in parliament, political parties, and election organizing institutions."

In addition, the achievement of women's political representation can also be measured by the gap in the number of women in parliament at the national and regional levels. Even though on the ASEAN scale, the achievement of political representation of Indonesian women ranks 5th out of 11 member countries. However, this situation is different from the number of women's political representation at the regional level.

“

“In the provincial and regency/city level legislative councils [DPRD], Indonesia is far behind ASEAN countries. Indonesia is still under Cambodia and even far below Laos. The number of political representation in the DPRD in Indonesia is around 16% in 2021. Compare this to Laos, which has reached 32%. Also compare, for example, with Vietnam, where the figure is 29%,” said Hurriyah.

In fact, Hurriyah added, Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam have not yet become democratic countries. This means that the progress of political representation of Indonesian women as a country with an electoral democratic system is not still fairly ordinary. "You could even say that it is much slower than for example our colleagues in the Philippines and also in Thailand," she said.

Hurriyah added that the quota policy factor played an important role in encouraging women's political representation in ASEAN countries. Vietnam, for example, is a country that still adheres to an autocratic government (one-party system) with women's political representation in the DPR reaching 30% and 29% at the local level. Meanwhile in Indonesia, this is still only a dream that has not been achieved.

"There is a problem where the implementation of the quota policy is still heavily influenced by political party interests. How do political parties, for example, treat quota policies solely as an administrative requirement to take part in elections? How about in the election management body, for example, the spirit of implementing the quota policy is also only seen as something that is morally encouraged, not a commitment to our constitution," said Hurriyah. []

NUR AZIZAH