There are administrative provisions in election regulations which if not implemented carefully have the potential to eliminate the right of citizens to vote in elections.

The right to vote for every citizen is basically protected by the constitution. The 1945 Constitution Article 27 paragraph (1) guarantees the equal political rights of citizens: All citizens have the same position before the law and the government with no exceptions. By referring to the article, the election law guarantees equal rights to vote for every citizen. During the four amendments, the article was included in the article that was maintained—no change.

However, the election law still has to regulate administrative provisions so that services for the fulfillment of the right to vote can run well. In practice, these administrative provisions—if not applied carefully—in fact have the potential to eliminate the right of citizens to vote. This can especially affect vulnerable groups of people, namely a number of citizens in certain socio-cultural conditions who have special challenges to access the voter registration process and voting.

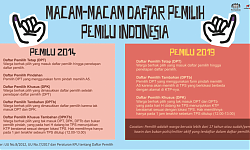

There are three discrimination issues in election regulations that have the potential to eliminate a person's voting rights that emerged during the 2019 Elections 2019 and 2020 Regional Head (Pilkada) Elections. These issues are, first, the possession of an electronic ID card as a requirement to be registered as a voter. Second, not being mentally disturbed as a requirement to be registered as a voter. Third, the limitations of switching arrangements and special voting methods.

Possession of an electronic ID card as a requirement to be registered as a voter

One of the things that often hinders someone from registering as a voter is the requirement for ownership of population documents, especially identity cards or electronic ID cards (KTP-el). To be registered, one must have an e-KTP. Vulnerable groups, such as indigenous peoples, transgender communities, and urban poor communities, who often find it difficult to obtain an e-KTP, cannot be included in the voter list and therefore cannot participate in voting in elections.

The provisions of this article were challenged by the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem), the Network for Democracy and Electoral Integrity (NETGRIT), the Center for Constitutional Studies (PUSaKO) Andalas University, as well as several individual applicants to the Constitutional Court (MK). In his petition, the petitioner asked the Constitutional Court to state that the article was contrary to the 1945 Constitution and had no binding force as long as it was not interpreted as “in the case of not having an electronic ID-card, another identity cards can be used, namely non-electronic ID cards, certificates, birth certificates, family cards, etc. marriage book, or other means of identification that can prove that the person concerned has ownership rights, such as a voter card issued by the KPU”.

The Constitutional Court in the decision No. 20/PUU-XVII/2019 states the phrase "electronic identity card" in Article 348 paragraph (9) of Law 7/2017 is contrary to the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia and does not have conditionally binding legal force as long as it is not interpreted as "including also a certificate of recording of electronic identity cards issued by the population and civil registration service or other similar agencies that have the authority to do so.”

The Constitutional Court's decision has not been able to accommodate voters who do not have an e-KTP. Possession of an e-KTP is an absolute requirement to be able to vote. The only substitute document that can be accepted is a certificate of having recorded population data. For those who do not have an e-KTP and have not recorded population administration, they cannot be registered as voters. Therefore, it can be said that this provision still has the potential for a person entitled to vote—but administratively a resident who is not registered or does not have an e-KTP—loses his/her right to vote.

Not being mentally/memory disturbed as a requirement to be registered as a voter

Another discrimination that exists in election regulations that have the potential to eliminate a person's right to vote is the provision that he or she is not mentally disturbed as a requirement to be registered as a voter. This provision was also challenged to the Constitutional Court. The Constitutional Court stated that this provision was contrary to the 1945 Constitution as long as the phrase "mentally/memory disturbed" was not interpreted as "experiencing a mental disorder and/or permanent memory impairment which according to mental health professionals has eliminated a person's ability to vote in general elections."

The KPU has also prepared a technical instrument that as long as there is no information from a medical professional stating that a person is suffering from a mental disorder, he or she has the right to be registered as a voter. However, this provision is sometimes interpreted differently by the ranks of election administrators. In 2018, the PKPU draft was reversed. People with mental disabilities or ODGJ are required to bring a letter of recommendation or a statement from a doctor or family member to be able to exercise their right to vote at TPS. The letter must state that the ODGJ is in good health. After receiving a protest from the Disability Coalition, this requirement failed to become a provision in the KPU regulations.

Even though it was not included in the PKPU, in February 2019, after the PKPU was established, there were still officials in the regions who stated that ODGJ could exercise their voting rights if they received a certificate from a doctor and a statement from their family. Therefore, this provision is still vulnerable or has the potential to eliminate a person's right to vote.

Limitations of switching voting arrangements and special voting methods

The arrangement for switching voting from the domicile of origin, which was actually meant to protect voting rights, turned out to be administratively difficult for some groups of voters. For example, voters with psychosocial disabilities who are receiving treatment at mental health institutions, for example, find it difficult to apply for a transfer form without facilitation from the election administrator or the orphanage. This is also experienced by prisoners and convicts who are serving time in prison.

This switching voter's right to vote should be accommodated if there is an alternative voting method other than voting at the TPS. According to International IDEA, special voting arrangements are needed to expand the opportunities for voters to cast their ballots and thereby facilitate the principle of universal suffrage. The arrangement of the voting method allows voters to vote in an alternative way other than coming directly to the polling station. These arrangements typically cater for special categories of voters, such as people with reduced mobility (e.g. elderly citizens in medical facilities; prisoners in correctional facilities; or polling officers working in constituencies that are not their native) or those who are not in the constituency where they are registered on election day (e.g. because they live abroad (International IDEA, 2021).

These various alternative voting methods are important to be regulated in the Election Law so that there is maximum facilitation of the voting rights of citizens with various special conditions.

MAHARDDHIKA & NURUL AMALIA SALABI

We map out the forms of voter suppression or interference with the right to vote in the Indonesian election. This article is the second in the series. Check out the articles in these series: