“General elections are a very important part of human rights (HAM) and their implementation cannot be separated from the rule of law. Elections provide an example of the practice of fulfilling human rights. Achieving a genuine and democratic electoral process is part of building a system of government that can ensure respect for human rights, the rule of law and the development of democratic institutions (European Union, 2016: 11).”

This is the opening written by the Chairperson of the Association for Elections and Democracy (Perludem), Topo Santoso, in an article entitled "Elections in Southeast Asia: Lessons from the 2019 Elections in Indonesia" which he wrote for Regional Support for Elections and Political Transitions (Respect) and presented at the “Regional Seminar and Workshop on The Role of Journalism in Supporting Democratic Elections in Southeast Asia” in Jakarta, 26 November 2019. From the opening, we can understand that elections are the embodiment of the fulfillment of human rights. Therefore, the implementation of elections should be a momentum to fulfill the human rights of every citizen in every process and stage. Elections should not turn into a four or five or six year event that actually causes casualties due to political conflicts that are capitalized by elites fighting for power.

Throughout 2019, 50 countries around the world held elections. In total, nearly two billion voters are eligible to vote to elect representatives in the legislature, as well as the executive. In Asia alone, elections were held in Thailand on March 24, Israel on April 9, India on April 11 to May 23 (CNN.com, April 25, 2019), Indonesia on April 17, the Philippines on May 13 (Al Jazeeraa, 2019), Afghanistan on September 28 (Thediplomat.com, November 15, 2019), and Sri Lanka on November 16 (Al Jazeera, November 13, 2019). Following are the 2019 election data in Asia.

|

No |

Country |

Election Type |

Number of voters |

|

1 |

Thailand |

Mid-term legislative election |

35.53 million |

|

2 |

Israel |

Legislative election |

6.3 million |

|

3 |

India |

National and local legislative elections |

Almost 900 million |

|

4 |

Indonesia |

Presidential, National and Local Legislative Elections |

192 million |

|

5 |

Filipina |

Mid-term Senate and Governor Elections and |

61 million |

|

6 |

Afghanistan |

Presidential Election |

More than 9.6 million |

|

7 |

Sri Lanka |

Presidential Election |

Almost 16 million |

Source: data from various sources, processed by rumahpemilu.org

From the data, it appears that the election in India is the election with the highest number of voters in 2019. There are almost 900 million registered voters to elect members of national and local parliaments across India. This number is 142 times the number of voters in Israel.

Indonesian Elections in Southeast Asia Region

Topo mentions in his writing that Thailand is one of the earliest democracies in Southeast Asia. The democratic government was established after massive street protests in Bangkok in 1992 that overthrew the military rule that had existed for nearly six decades. The process of democratization in the political field was then institutionalized in the 1997 constitution, which was considered by many to have strengthened Thailand's democratic transition process (p.1).

The transition period from autocratic to democratic government also occurred in Indonesia. Democratic government developed after Suharto's fall from power. In May 1998, which is remembered as the day of reform, various groups, especially students, took to the streets demanding that Suharto step down. Twenty years later, namely 2018, according to Topo, Indonesia has succeeded in developing as one of the pillars of democracy in the Southeast Asian region. Indonesia maintains the achievements of the 1998 Reformation, one of which is limiting executive power: a maximum of two terms with a term of office of five years. Indonesia has also succeeded in holding regular elections with a cycle of once every five years. The 2019 Simultaneous Election is Indonesia's fifth post-Reformation election.

If referring to the Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index (IDUI) 2016, the Indonesian election during the Reformation period was considered one of the most democratic elections in the Southeast Asian region, although according to IDUI there is no country in Southeast Asia that has a full democracy. Indonesia is in first place with a score of 6.97. Below Indonesia are the Philippines with a score of 6.94, Malaysia 6.54, Singapore 6.38, Thailand 4.92, and other Southeast Asian countries.

Still in this index, in the election category, there are only two countries with election scores above 7 in Southeast Asia, namely Indonesia and the Philippines. The Philippines' score is 9.17 and Indonesia's 7.75.

Unfortunately, as we can find in Topo's writings, the trend of democracy in Southeast Asia tends to go backwards. In Myanmar, for example, a country that used to be a source of hope and inspiration for other countries in Southeast Asia to make the transition to democracy, has now become a bad example of the practice of intolerance and oppression accompanied by violence against minorities. New hope is now emerging in Malaysia, which is currently reforming the electoral system and the institutional system for organizing elections.

“Only in Malaysia are green shoots emerging as we approach the one-year anniversary of the election setback. The process in Malaysia brings hope for reform and maintaining democratic norms in Malaysia,” wrote Topo (p.3).

Learn from the Indonesian election

During the New Order era under Suharto, elections in Indonesia, Topo wrote, were considered undemocratic. If there should be a “certain process, uncertain outcome” in the general election, in the New Order election, the opposite was true. The election results have been determined, along with the allotted parliamentary seats for each political party participating in the election.

Therefore, in Reformasi, reforming the Indonesian electoral system is one of the priority agendas. The election management institution is designed as a national, permanent and independent institution, as stated in the third amendment to the 1945 Constitution (Tirto.id, October 14, 2019), as well as political space to participate in elections in the first general election after the Reformation, namely 1999, was widely opened. As a result, there were 48 political parties participating in the 1999 General Election, compared to only three during the New Order era as a result of the party fusion policy.

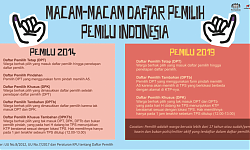

Indonesian elections from time to time experience changes. Topo raised the issue of simultaneous elections in his writings. If in the first four elections after the Reformation period the executive and legislative elections were not held simultaneously on the same day, in 2019, five elections were held simultaneously. The five elections in question are the Presidential Election, the Election of the People's Representative Council (DPR) of the Republic of Indonesia, the Election of the Regional Representatives Council (DPD), the Election of the Regional DPR (DPRD) of the Province, and the Election of the Regency/City DPRD.

The 2019 Indonesian Simultaneous Elections, according to Topo, deserve to be a lesson for other countries, especially countries in the Southeast Asian region. In fact, the Indonesian Simultaneous Election is the largest single-day election in the world, with 192 million more voters and 800,219 polling stations (TPS) across Indonesia. According to the Minister of Home Affairs Regulation No.137/2017 dated December 29, 2017, the total area of Indonesia is 1.91 million square kilometers.

Standards of democratic election

To assess whether the implementation of elections in a country is democratic, a measuring instrument in the form of democratic election standards is needed. Referring to the standards adopted by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance (IDEA) in 2002, there are 15 international standards as minimum requirements in the legal framework to ensure democratic elections. The standards are: (1) structuring the legal framework, (2) the electoral system, (3) setting boundaries, such as electoral districts and electoral boundaries, (4) the right to vote and be elected, (5) election management institutions, (6) registration voters and voter lists (7) access to ballot papers for political parties and candidates, (8) democratic election campaigns, (9) media access and freedom of expression, (10) campaign funds and campaign spending, (11) voting, (12 ) vote counting and tabulation, (13) the role of representatives of political parties and candidates, (14) election observers, and (15) election compliance and law enforcement.

These standards, Topo noted, were taken from various international and regional declarations and conventions, such as the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the 1960 International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the 1950 European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and human freedoms, and the Charter Africa 1981 on Human and Community Rights.

Furthermore, there are 20 mandatory things that must be present in elections, namely: (1) Right and opportunity to participate in public affairs; (2) Right and opportunity to vote; (3) Right and opportunity to be elected; (4) Periodic elections; (5) Universal suffrage; (6) Equal suffrage; (7) secret ballot; (8) Free from discrimination and equal under the law; (9) Equality between women and men; (10) Freedom of association: (11) Freedom of assembly; (12) Freedom of movement; (13) Freedom of opinion and expression; (14) Right to security; (15) Transparency and the right to information; (16) Prevention of corruption; (17) The rule of law; (18) The right to an effective remedy; (19) The right to a fair and open hearing; and (20) Guarantees from the state to fulfill these rights (International IDEA, 2014: 37-58).

“The 14th obligation very clearly shows that every country holding elections must guarantee the right to the security of every human being in the election process, such as candidates, election administrators, civil society organizations, the media and voters. This obligation also affirms the safety of people from injury or illness, as well as guarantees for freedom and the prohibition of arbitrary arrest and detention. This guarantee is actually a guarantee of the ICCPR (International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights) which is indeed one of the references for international obligations regarding elections,” said Topo.

In addition, International IDEA also provides 21 components that must be included in the electoral law in each country (International IDEA, 2014: 59-285). The 21 components are as follows: (1) The structure of the legal framework; (2) Electoral system; (3) Boundary delimitation; (4) Political parties; (5) Political funding; (6) Election management; (7) Gender equality; (8) Equal opportunities for minority and marginalized groups; (9) Equal opportunities for persons with disabilities; (10) Election observers; (11) Voter education; (12) Conditions for voting rights; (13) Voter registration; (14) Candidate registration; (15) Media environment; (16) Election campaigns; (17) Media campaigns; (18) Voting procedures; (19) Management of vote counting and recapitulation; (20) Electoral justice; and (21) Election violations. In Topo's writing, he discusses three components, namely the structure of the legal framework, election management, and election justice.

Structure of Indonesia's electoral legal framework

The Handbook released by the United Nations (UN) on Legal, Technical and Human Rights Aspects in Elections highlights the importance of principles of the rule of law such as legal certainty, accessibility, coherence, timeliness and stability of the legal framework. As Topo wrote, the legal framework for elections is very important as the basis for the implementation of elections. Simply put, there can be no fair and democratic elections without a legal framework for fair elections and regulating the stages of elections in a fair and democratic manner. For example, if electoral law restricts citizens' freedom of assembly, association, opinion, movement or expression, then elections will limit the exercise of political and civil rights.

There are at least five things that must be regulated in the legal framework of elections, namely guarantees that elections are held periodically, protection of citizens' political rights both to vote and to be elected, legal certainty and coherence of all regulations, prohibiting discrimination based on gender, and ensuring equal protection under the law.

These standards, in Indonesia, are harmonized with the existing electoral legal framework. The legal framework for elections in Indonesia is contained in seven basic types of laws and regulations, namely (1) the 1945 Constitution; (2) Law no. 7/2017 concerning General Elections; (3) various regulations of the General Elections Commission (KPU); (4) various regulations of the Elections Supervisory Body (Bawaslu); (5) Regulation of the Election Organizing Ethics Council (DKPP) regarding the general election code of ethics; (6) Regulations of the Supreme Court regarding the Settlement of Election Administration, and (7) Regulations of the Constitutional Court regarding disputes over election results.

All legal frameworks, except for the 1945 Constitution, provide time limits for all stages of the election as well as the handling of election violations and disputes, as well as handling violations of the ethics of election administrators. Topo assesses the certainty of time as a guarantee that the implementation of elections will be carried out on time and periodically, and provides legal certainty for all parties.

The problem with the Indonesian legal framework is the stability of the legal framework. In Indonesia, the Election Law always changes or is amended every five years, especially 1-3 years before the election. In fact, in special situations, legal changes occur as a result of testing norms in the law at the Constitutional Court (MK). This creates legal uncertainty or at least consequences for political parties and election administrators. Indeed, within the Indonesian legal framework, the Constitutional Court has the authority to examine the constitutionality of all laws.

“This note also relates to the context of coherence in the electoral legal framework. Supposedly, all election provisions in the legal framework are coherent and not contradictory, and there should be no legal vacuum because it will confuse election stakeholders. However, in some cases, there are indeed coherence problems in our electoral regulations so that they must be corrected either through legislative review, revision by the executive, or judicial review," said Topo.

In general, in relation to the provisions that must exist in the international electoral law framework, Indonesian law has guaranteed the protection of citizens' political rights to vote and be elected, prohibit discrimination based on gender, and ensure equal protection before the law. In fact, in Law No. 7/2017, there are special measures for women to be involved in political participation.

Indonesian election management

Referring to International IDEA, Topo briefly stated that the administration of elections with all their complexities is the responsibility of the election organizers, and to ensure that elections are held fairly, impartially and in accordance with applicable laws, it is necessary to have an independent authority set up to 'supervise' selection process. The legal framework must stipulate provisions so that there is no conflict of interest within the election management body, recruitment issues, tenure, wages, duties, powers, qualifications, and reporting structure for election administrators.

“Staff must be isolated from political bias and pressure at all levels, and there is only one highest line of authority defined,” wrote Topo (p.9).

A good election organizer meets the following criteria. One, there is a legal basis that guarantees that election administrators can act independently. Two, have the authority to make regulations in accordance with the principles of organizing elections. Three, the recruitment of election administrators provides access to everyone and the election is based on a merit system. Fourth, election administrators work in a transparent and accountable manner. Fifth, the availability of a mechanism to review decisions or regulations made by election administrators, which prioritizes the restoration of citizens' rights.

Unlike in several other countries, election management in Indonesia is carried out by three institutions, namely the KPU which functions to carry out all stages of the election, Bawaslu as an election supervisory and judicial institution, and DKPP as an ethical judiciary institution for election management. If the hands of KPU and Bawaslu reach TPS, DKPP only has representatives up to the provincial level.

The existence of three electoral institutions in Indonesia, in Topo's view, is in line with international election standards for three reasons. First, the requirements to become members of the KPU, Bawaslu, and DKPP are strictly regulated in the Election Law, which states that candidates may not have affiliations with political parties. Second, except for the selection of DKPP members, the recruitment process is carried out by a selection team from various circles of civil society, although for the RI KPU, in the final process the candidates are selected by members of parliament at the national level. Third, all citizens with sufficient qualifications can take part in the selection process. Fourth, the recruitment process is carried out openly and monitored by civil society. Fifth, the opening of space to convey input from the public to the selection team regarding the track records of candidates for election organizers.

"So, all of this is to guarantee the selection of KPU and Bawaslu members from the center to regions that are independent, credible and capable," wrote Topo (p.21).

In addition, Indonesia's legal framework has also provided a basis for the KPU, Bawaslu, and DKPP to act independently. Each institution can make its own regulations, in consultation with the DPR RI, according to the norms in the Election Law. If the regulations made by the institution are deemed to violate the law, then the parties who meet the legal standing can submit a judicial review to the Supreme Court (MA). Decisions issued by the KPU can also be disputed with Bawaslu. If the party submitting the dispute is not satisfied with the Bawaslu decision, then the party concerned can file an appeal to the State Administrative Court (PTUN).

“A material test of the PKPU (KPU Regulation) has been carried out in Indonesia. For example, the judicial review of PKPU which contains norms prohibiting prisoners from becoming candidates for members of the DPR/DPD/DPRD,” said Topo (p.21).

Unlike the case with KPU decisions which can be challenged, DKPP decisions are final and cannot be corrected.

Electoral justice in Indonesia

“The implementation of the election is clearly inseparable from various problems, lawsuits, complaints, criminal reports and so on. All of these require resolution, because otherwise the implementation and election results can be doubted,” Topo wrote in his writing (p.11).

He further explained that the electoral justice system refers to the method or mechanism taken by a country to ensure and verify that the actions, procedures and decisions of election administrators are in accordance with the legal framework, in order to protect or restore the right to vote and not to be elected. Electoral justice plays a fundamental role in the ongoing democratization process and promotes the transition from the use of force to legitimate means of resolving political conflicts. In other words, an electoral justice system that is able to resolve political conflicts through legal mechanisms and guarantees full compliance with the law will help democracy develop.

Regarding the electoral court itself, it is clearly stated that the judiciary must be free from corruption and partisan influence. There are six measures of pros and cons of an electoral justice institution, namely focusing on the restoration of rights, being able to administer legal courts that provide effective remedies, providing judicial review of administrative actions and decisions of election administrators related to the electoral process, the existence of provisions that guarantee the independence and impartiality of the judiciary, the judicial process is open to the public, and the availability of access for all election stakeholders to electoral justice mechanisms.

In the 2019 Simultaneous Elections, until May 28, 2019, Bawaslu received 14,462 findings and 1,581 reports of election violations. The findings are election violations found by the election supervisory ranks under the command of the RI Bawaslu, while the reports are election violations reported by the public. From the reports and findings of these violations, 533 cases fall into the category of election crimes, 12,138 cases of election administration violations, 162 cases of violations of the electoral code of ethics, and 1,096 other violations. As a result of the follow-up to the handling of violations, as of May 2019, there were 106 criminal case decisions that have been decided with permanent legal force (p.23).

The provisions in the Election Law, violations of election crimes are processed by the district courts of the first level. Furthermore, the litigating parties can file an appeal to the High Court with a final and binding decision.

In his writings, Topo expressed his view that the legal framework for elections in Indonesia has sought to adopt international democratic election standards. Indonesia has an electoral justice system that seeks to restore the rights of election participants and correct mistakes in the implementation of the election stages, laws that protect the right to vote, guarantee equality between men and women, and the right to participate in public affairs.

In fact, the Indonesian Election Law has categorized six types of election violations. The six categories include election crimes, election administration violations, code of ethics violations, election process disputes, election administration disputes, and election results disputes. The law regulates the mechanism for filing lawsuits, institutions authorized to adjudicate, sanctions, and the time limit for the settlement of each type of violation or dispute. The settlement process in each court is also encouraged to be open to the public, with decisions that can be read on the websites of each institution.

Indonesian Simultaneous Elections and their alignment with international electoral principles

Based on the explanation described by Topo in his writing entitled “Lessons from The 2019 Elections in Indonesia”, we can see that the implementation of the 2019 Simultaneous Elections in Indonesia, in particular the legal framework, election management, and electoral justice, is carried out with democratic electoral standards and components, formulated by International IDEA. Even though there are still shortcomings due to the complexity caused by the simultaneous election, Topo praised the Indonesian election organizers for successfully holding the 2019 Simultaneous Election with all its complexities: 16 political parties participating in the election, five types of elections on the same day simultaneously throughout Indonesia, 192 million voters. The complexity, although not implicitly stated, is suspected by Topo as the cause of the death toll from the election organizers.

“If elections are conducted simultaneously in one day to select many positions (five positions / 5 voting boxes), this will have an impact and have implications for the workload and health and safety of election officials if it is done manually, taking into account the time limit for the counting process and recapitulation as well as many documents that must be completed. This is compounded by the many demands, including transparency, accountability, and fairness of elections demanded by election stakeholders, as well as the accompanying criminal threats when there are mistakes in carrying out their duties,” explained Topo (p.26).

Topo compared Indonesia's simultaneous elections with the Philippines. Although the Philippines also elects the executive and the legislature on the same day, even to the local level executive, no election organizers have died during the simultaneous elections. The reason, according to Topo, is the use of electronic vote counting technology or e-counting.

Topo assessed that the use of e-counting technology in the 2019 Philippine Simultaneous Elections was a success. Even though there were reports of 400 to 600 e-counting machines crashing on polling day, random manual audits conducted a few days before polling day were able to show that machine counting resulted in accurate election results. The accuracy rate for vote counting for the Senator Election is 99.9971 percent, the Parliamentary Election 99.9946 percent, and the Mayor's Election 99.9941 percent.

Regarding these problems, and by borrowing lessons from the 2019 Philippine Simultaneous Elections, Topo recommends two things. First, divide the election into national elections and local elections. Second, using and optimizing technology in the election process, especially in the process of counting and tabulating votes. The two recommendations are expected by Topo to provide guarantees for safety, health and a reasonable workload for election organizers.

References

Al Jazeeraa. 2019. “How the World Votes: 2019”. Interactive Data in https://interactive.aljazeera.com/aje/2019/how-the-world-votes-2019/index.html. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:15 WIB.

Al Jazeera. 13 November 2019. “Sri Lanka’s presidential election 2019: All you need to know”. Special coverage in https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/11/sri-lanka-presidential-election-2019-191111123802911.html. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:28 WIB.

Al Jazeera. 29 September 2019. “Voter turnout falls sharply in Afghan presidential election”. News in https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2019/09/voter-turnout-falls-sharply-afghan-presidential-election-190929073943812.html.

CNN.com. 25 April 2019. “Indian officials travel 40 miles into forest so one man can vote”. Special coverage in https://edition.cnn.com/india/live-news/india-election-2019-latest-updates-intl/index.html. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:19 WIB.

DW.com. 2019. “Afghan election sees just one in five voters cast ballot”. News in https://www.dw.com/en/afghan-election-sees-just-one-in-five-voters-cast-ballot/a-50629649. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:55 WIB.

IFES. Published data in http://www.electionguide.org/countries/id/201/. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 13:04 WIB.

Rappler.com. 12 May 2019. “2019 Elections: 61 million voters expected to troop to the polls nationwide”. News in https://www.rappler.com/nation/politics/elections/2019/230366-voters-troop-polls-2019-philippine-elections. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 11:58 WIB.

Sirivunnabood, Punchada. (2019). Report of ISEAS Yusof Ishak Institute. Report can be viewed via the link https://www.iseas.edu.sg/images/pdf/ISEAS_Perspective_2019_44.pdf. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:02 WIB.

The Diplomat. 15 November 2019. “Prolonged Patience: Elections in Afghanistan”. Special coverage in https://thediplomat.com/2019/11/prolonged-patience-elections-in-afghanistan/. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:59 WIB.

The New York Times. 22 May 2019. “India Election 2019: A Simple Guide to the World’s Largest Vote”. Special coverage in https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/world/asia/india-election.html. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:37 WIB.

Times of Israel. 17 September 2019. “Voter turnout slightly outpaces April elections”. News in https://www.timesofisrael.com/voter-turnout-slightly-outpaces-april-elections/. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 12:44 WIB.

Tirto.id. 14 October 2019. “Amandemen UUD 1945: Sejarah & Isi Perubahan Ketiga Tahun 2001” [Amendment to the 1945 Constitution: History & Contents of the Third Amendment of 2001]. Article in https://tirto.id/amandemen-uud-1945-sejarah-isi-perubahan-ketiga-tahun-2001-ejHB. Accessed on 17 December 2019, at 15:42 WIB.