Election monitoring in Indonesia is a new phenomenon at the end of the 20th century. Globally, the first election monitoring was conducted by the Commission of European States on General Elections in the disputed areas of Wallachia and Moldova in 1857, election observers in Indonesia only existed in the 1997 elections under Suharto. At that time, it was not an easy and safe period for observers.

1997 Elections, infectious spirit under an authoritarian regime

Komite Independen Pemantau Pemilihan [Independent Election Monitoring Committee] (KIPP) is the first election monitoring body in Indonesia. Founded in 1995 by activists, journalists, academics, and intellectuals, as a response to the New Order government which often manipulated elections.

The formation of KIPP was inspired by the formation of The National Citizens' Movement for Free Elections (NAMFREL) in 1983 by a number of activists cum entrepreneurs in the Philippines. NAMFREL exists to respond to the authoritarian government of Ferdinand Marcos and contribute to overthrowing the regime.

Once, in February 1995, Rustam Ibrahim, Head of the Institute for Economic and Social Research, Education and Information (LP3ES) attended the Asia-wide Election Monitoring Conference organized by NAMFREL and The National Democratic Institute (NDI) in Manila. Upon his return from Manila, he initiated the establishment of KIPP. It was agreed that Gunawan Muhammad, editor of Tempo magazine, was elected as the chairman of KIPP.

Monitoring elections for the first time in the absence of regulations that allow for election observers is not easy. KIPP had to hold a big meeting and training members in Bangkok. Luckily, KIPP received support, both financial and consulting for the creation of an election monitoring module from NDI.

The 1997 election monitoring, as admitted by one of the KIPP activists at the time, Ray Rangkuti, aimed to prevent Golongan Karya (Golkar) from coming to power again. Therefore, KIPP election monitoring is directed to focus on noting violations committed by Golkar, the Armed Forces of the Republic of Indonesia (ABRI), and the bureaucratic apparatus. From this monitoring, KIPP noted that there were at least more than 10,000 election violations to win back Golkar.

This history makes the KIPP election monitoring for the first time unable to be called in accordance with the principle of election monitoring, namely non-partisanship. If non-partisan, the recording of election violations should also be carried out on other election participants.

1999 Elections, the spirit of guarding the democratic transition

The 1999 election was the first general election in the Reformation era that determined Indonesia's democratic transition process. The spirit of forming a new and clean order from the oligarchy after the collapse of the New Order triggered the participation of civil society to participate in monitoring elections. Everyone feels interested and wants to be involved.

13,260 people voluntarily registered as KIPP observers. Other election monitoring organizations have also emerged, such as the University Network for Free Elections (UNFREL) and Forum Rektor [Rector's Forum].

The first, UNFREL, is an election monitoring network initiated by a network of lecturers and students throughout Indonesia. UNFREL was formed on 5 October 1998, with Todung Mulya Lubis selected as its first coordinator. Through this network, 100,000 volunteers in 22 of 27 provinces monitored the stages of the 1999 general election.

Meanwhile, the Rector's Forum is an election monitoring network formed by the Rectors of Trisakti University and the Bandung Institute of Technology on November 7, 1998. The idea of the Rector's Forum was sparked after a rectors' conference was held which was attended by 174 rectors throughout Indonesia. This forum not only monitors voting, but also supervises voter education programs and tabulation of election results in a parallel way.

Apart from domestic election observers, election observers also come from other countries. No less than 15 representatives of European countries, such as Germany, Britain, France, Italy, and the Netherlands participated in monitoring the 1999 elections. They are members of the European Union Observation Unit institution.

There are also international election observer institutions that monitor, including NDI, The Carter Certer, Asia Network For Free Elections (ANFREL), National Citizen Movement For Free Elections (NAMFREL), and International Republican Institute (IRI).

In the notes of Tempo's June 28, 1999 edition, it is known that money politics, and intimidation of voters and election organizers were found by many election observers in the 1999 Elections.

2004 Elections, thematic election monitoring

In the 2004 general election, many election observers chose their respective focus of monitoring. There are monitoring agencies that monitor voter registration, women's nominations, campaign stages, campaign funds, access elections, distribution logistics, and also the media. The media became one of the focuses of monitoring in 2004 because there were fears of an imbalance in reporting on election participants by the media.

There are also more institutions that monitor elections. It is noted that the KPU gave accreditation to 25 monitoring institutions, including the Center for Electoral Reform (CETRO), the Voter Education Network for the People (JPPR), Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), the General Election Center for Access for Persons with Disabilities (PPUA Penca), LP3ES, and Forum The Indonesian Parliamentary Concerned Society (Formappi).

CETRO is important to elaborate. This institution was founded by former UNFREL leaders and activists who wanted to remain active in electoral reform. As is well known, UNFREL disbanded after the 1999 General Election. CETRO was active in conducting studies and advocacy, he contributed to the direct presidential election, new constitution, and access elections.

JPPR is also important. JPPR was founded in 1998 by activists of the Indonesian Islamic Student Movement (PMII). In that year, PMII, through JPPR, conducted voter education, but did not carry out monitoring. The new monitoring was carried out in the 2004 General Election, in connection with the change in the orientation of donor funding to election monitoring.

144,000 people are registered as election observers organized by JPPR. This number is far more than the number of observers for the KIPP election, which fell drastically from the 1999 election, which was only 145 people. JPPR monitors focus on monitoring money politics, campaigns, and post-polling day monitoring.

Another election monitoring agency that is important to elaborate is the PPUA Penca. PPUA Penca is a coalition of various disability organizations at the national level, such as Persatuan Penyandang Disabilitas Indonesia [Indonesian Association of Persons with Disabilities] (PPDI), Himpunan Wanita Disabilitas Indonesia [Association of Indonesian Women with Disabilities] (HWDI), and Persatuan Tuna Netra Indonesia [Indonesian Blind Association] (PERTUNI). The goal is to advocate for the political rights of persons with disabilities in elections.

PPUA demands equal rights to be elected and to vote for people with disabilities, access to polling stations, and encourages people with visual impairments to be accompanied by people of their own choosing in voting. In the previous election, it was the election committee that voted for disability.

In general, in terms of the number of election observers in the 2004 General Election, the number of election observers decreased compared to the 1999 election. The decrease in the number of election observers is thought to be caused by public dissatisfaction with the results of the 1999 General Election. The government resulting from the 1999 General Election is seen as not producing significant changes to Indonesia's democratic transition process.

In the book Oligarchy (2020) written by Coen Husain Pontoh, Abdul Mughis Mudhaffir and friends, for example, the authors consider that the 1999 Reformation has even revived the old oligarchy, so that those who competed in the 2004 General Election were the old oligarchy, the new oligarchy, and the new oligarchy with ties to the old oligarchy.

2009 Elections, election monitoring is increasingly institutionalized

Fewer than the 2004 election, there were only 18 monitoring institutions accredited by the KPU in the 2009 election. The 18 election monitoring institutions were KIPP, CETRO, JPPR, Formappi, Perkumpulan untuk Pemilu dan Demokrasi [Association for Elections and Democracy] (Perludem), Indonesia Parliamentary Center (IPC), PPUA Penca, Pusat Kajian Politik [Center for Political Studies] (Puskapol) University of Indonesia, Demos, ICW, Pusat Studi Hukum dan Konstitusi [Center for Law and Constitutional Studies] (PSHK), Indonesia Budget Center (IBC), Soegeng Sarjadi Syndicate (SSS), Consortium for National Law Reform [Konsorsium Reformasi Hukum Nasional] (KRHN), Seknas Forum Indonesia untuk Transparansi Anggaran [National Secretariat of the Indonesian Forum for Budget Transparency] (FITRA), Transparency International Indonesia (TII), and LP3ES.

During the 2009 election, monitoring was also carried out on the handling of election violations and disputes. One of the institutions that focused on monitoring was Peludem, an institution founded in January 2005 by former members of the Election Oversight Committee for 2004. Several figures were involved in the process of establishing Perludem, namely Bambang Wijayanto, Iskandar Sondhaji, Budi Wijarjo, Andi Nurpati, Didik Supriyanto, Topo Santoso, Nur Hidayat Sardini, and Siti Noordjannah Djohantini.

Institutions such as ICW and TII have also expanded their monitoring of electoral corruption. There are at least three things in the sub-focus of monitoring election corruption, namely criminal money politics violations, campaign finance violations, and violations of the use of public facilities.

2014 Election, information technology-based monitoring

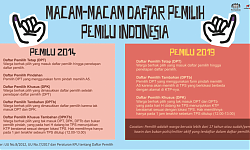

In the 2014 election, there were 19 election monitoring institutions accredited by the KPU. Some monitoring institutions are still the same as in 2009, but there are new monitors, namely Garda Santri Nusantara, Migrant Care, Kemitraan [Partnership], Aliansi Jurnalis Independen [Alliance of Independent Journalists], and Gerakan Mahasiswa Kristen Indonesia [Indonesian Christian Student Movement].

Also in this election, monitoring technology began to develop. Previously, monitoring only used check lists, in 2014, monitoring technology has been used. The use of information technology in monitoring is in line with the familiarity of the community with information technology. And also, it is believed that information technology can increase people's active participation in elections.

AJI together with iLab and Perludem, for example, developed the MataMassa application. MataMassa receives report input from the user community, then processes the report and displays it in a new report.

Civil society led by Ainun Nadjib also initiated Kawal Pemilu [Election Guard] which tabulates the results of vote counting at TPS which is published by the KPU through its website. The results of the tabulation of the vote count will be used as a comparison for the results of the tiered recapitulation of the KPU.

Election monitoring in 2014 also increased in focus. There are institutions that monitor social media and technology devices. PoliticaWave is one of them. They monitor social media conversations about politics in real time.

2019 Elections, election hoaxes undermine the work of election observers

The initiation of monitoring technology is increasingly developing in the 2019 Election. Kawal Pemilu has been revived by the Network for Democracy and Electoral Integrity (Netgrit), an election monitor founded by former KPU members for the 2012-2017 period, namely Hadar Nafis Gumay, Ferry Kurnia Rizkiyansyah, and Sigit Pamungkas

The existence of the 2019 Kawal Pemilu should be able to reconcile the turbid atmosphere after the stipulation of the vote recapitulation results by the KPU. Because, the results of the recapitulation of the two votes are not much different, and the winner of the election remains the same. However, massive election hoaxes, the level of digital literacy of voters, and the decreasing number of election observers, erupted demonstrations in front of the Bawaslu building for several days, protesting the election results.

Hoaxes have indeed become one of the focuses of monitoring the 2019 Election which has been in the spotlight. The Wahid Institute, Masyarakat Anti Fitnah Indonesia [Indonesian Anti-Defamation Society] (Mafindo) monitored election hoaxes circulating on social media. In total, election monitoring institutions registered and accredited by Bawaslu in 2019 were 51. More than the 2014 election.

Election monitoring challenges

Although there were more election monitoring bodies involved, they were unable to organize many observers. For example, Kawal Pemilu Jaga Suara 2019 lacked election observers, so they had to take a photo of C1-Copies from the KPU RI website.

There are several challenges to election monitoring. First, the lack of monitoring funding assistance. Second, the requirements for registration and accreditation of election observers are increasing. Third, there is no protection for election observers who report cases of election violations such as money politics.

Election observers are election actors. One of the spaces that civil society can take is to participate in electoral democracy. Throughout the history of Indonesia's election observers' journey, it has been shown that election observers have contributed to the openness of election administrators to election process data and information, as well as elections that are increasingly inclusive of women, people with disabilities, indigenous peoples, and other vulnerable groups.