In short, a presidential system is a system of government that gives top power to a president. Not all presidents are directly elected by the people through general elections, but they can also be elected by the people's representative body. Indonesia has run a presidential election model by the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR) in 1999, then the president has been directly elected by the people since the 2004 general election.

The History of Presidential System

Presidential as a government system was born as an alternative, both to the monarchical system of government (absolute or constitutional) and the parliamentary system (republican or monarchy). Its historical origins and theoretical background can be found in monarchical rule. The idea that one person can hold the posts of head of state and head of government in a presidential system is similar to the concept of a traditional monarchy.

In terms of the historical evolution of the theory of forms of government, presidential takes on a republican dimension as opposed to monarchy. Whereas in a republican order, it takes the dimension of democracy as opposed to an aristocracy.

An important concept of a presidential system is the separation of powers. Trias politica initiated by John Locke became the heart of the presidential concept. There are three branches of power, namely executive, legislative and judicial.

Because of this division of power, even though there is a large concentration of authority in the hands of a unipersonal organ, namely the presidency, which can easily make the presidency leading to authoritarian deviation, the presidency should still be able to meet democratic expectations. The reason is that the source of the legitimacy of a president's power is the people through elections, and the legislative body which also functions to carry out checks and balances is also filled by people who are elected by the people through elections.

“Obviously, not every source of legal-rational legitimacy and not every type of election itself is democratic. However, in presidential cases, these two elements are generally related to the perspective of democracy. Compared to traditional and charismatic sources of legitimacy, presidential sources of legitimacy are impersonal. And unlike the autocratic alternative, the president's legitimacy flows from the bottom up as an expression of the citizens' political autonomy," as quoted from Fierro and Salazar's article, Presidentialism page 2.

In general, there are six characteristics of a presidential system that distinguish it from other government systems such as parliamentary and semi-presidential systems. First, the government and the state are led directly by the president. Second, the president as the executive body is appointed through the election of the people or the people's representative body. Third, the president has the privilege or what is called the prerogative to appoint and dismiss ministers or ministerial-level officials. Fourth, the minister is directly responsible to the president. Fifth, the president has no responsibility to the legislative power. Sixth, the president cannot be fired by the legislature so that the president is the chief executive with a fixed term of office. In Indonesia and several countries in the world, it is permissible to impeach the president by the legislature, but this is very rare because impeachment can only be carried out if there are extraordinary circumstances.

Ambiguity of presidential candidacy threshold

In the implementation of the presidential system in Indonesia, with the main reason being to ensure the president gets majority support in parliament so that there is no government deadlock, a presidential nomination threshold is applied, which is often referred to as the presidential threshold. An incorrect term is used, because the presidential threshold refers to the electability of a presidential candidate, not a presidential nomination.

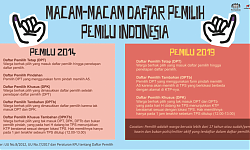

The presidential nomination threshold has been applied in the presidential election (pilpres) in Indonesia since the 2004 Election, or since the first time the president was directly elected by the people. At that time, after the third amendment to the constitution, through Law No.23/2003 on Presidential Elections, the DPR (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat) imposed a presidential nomination threshold of 15 percent of the total number of DPR seats, or 20 percent of the nationally valid votes in the DPR election. However, in Article 101 of the law, special waivers are granted for the 2004 presidential election. Political parties or a combination of political parties in the DPR that have a minimum of 3 percent of the total number of seats in the DPR can nominate a presidential-vice presidential candidate pair (paslon). The relief was also given to the party or coalition of parties that succeeded in obtaining at least 5 percent of the national valid votes in the 2004 DPR election.

The threshold for presidential nominations was then increased in the 2009 Presidential Election. Article 9 of Law No. 42/2008 concerning Presidential Elections stipulates that a candidate pair is proposed by a party or coalition of political parties participating in the election that has a minimum of 20 percent of the total seats in the DPR, or 25 percent of the national valid votes in the previous DPR Members election. This rule is maintained until the 2019 presidential election.

According to Scott Mainwaring, in countries that implement a presidential system of government and a democratic political system, or a combination of the two, it is termed presidential democracy, which has two distinguishing characteristics. One is that the head of government is elected independently of the legislature. That is, legislative elections or post-election negotiations do not determine executive power. This distinction emphasizes that the presidential election is not part of the negotiation process in the legislature, both before and after the election. Thus, the threshold for presidential nomination is an anomaly or contrary to the presidential democratic system. The president is not the product of the negotiation of the legislative body.

Djayadi Hanan, in his opinion entitled “Ambang Batas Presiden [Presidential Threshold]”, even assessed that the regulation on the threshold for presidential candidacy makes Indonesia unable to be called a country with a pure presidential system. The legislators, using the wrong logic, have made legislative elections a prerequisite for the presidential election.

The regulation on the presidential candidacy threshold has been repeatedly challenged to the Constitutional Court (MK), but none of the petitions have been granted. In October 2018, the Constitutional Court rejected and did not grant four cases of judicial review of the presidential-vice presidential nomination threshold contained in Article 222 of Law No. 7/2017 concerning Elections.

The reasons of the Constitutional Court, the Court is considering strengthening the presidential system, there is no change in the state administration that makes the Constitutional Court have to change its stance, and the threshold for presidential candidacy is an open legal policy which is the right of legislators. In fact, the strengthening of the presidential system should be carried out without having to cross the concept of a presidential democratic system which is officially implemented in Indonesia.

Presidentialism and the challenges of extending tenure

In many countries with presidential systems, the test for democracy is often an extension of the president's term of office. In Latin America, the presidents of several countries have amended the constitution to extend the term of office of the president. In Bolivia, for example, in 2016, through a referendum, former president Evo Morales changed the 2009 constitution which only allowed the president to serve two consecutive terms. The maximum term limit has been removed. This rule has changed significantly from the pre-2009 constitution which only allowed a president to serve for one five-year term.

In Colombia, President Alvaro Uribe is trying to change the law to be able to run for a second term. However, these efforts were not successful.

In Kazakhstan, there is a law that stipulates that President Nazarbayev can serve for life, but that the next president is limited to a maximum of two terms.

In Peru, where the president is not allowed to run for office directly after the first term (as well as family members who cannot replace the president immediately after his term ends), this provision is being tried to be amended. However, civil society steadfastly maintains that the regulations do not change, because without these restrictions, given the enormous power of the Peruvian president, elections will produce a dictator.

The same winds of testing are trying to blow over Mexican democracy. The six-year, non-renewable presidential term is proposed to be amended. In fact, this regulation is the fruit of the nation's history after the end of President Porfirio Diaz's three-decade rule.

The same history led Indonesia to the first constitutional amendment to Article 7 of the 1945 Constitution which limits a maximum of two terms for the president, either successively or intermittently. This regulation was pushed by several parties to be broken on the grounds that the current president is working well, avoiding polarization in the presidential election, as well as providing an opportunity for President Joko Widodo to resolve the Covid-19 pandemic and development delays due to the pandemic.

The proposal was rejected by various groups, especially activists on democracy issues and academics. In fact, a former judge of the Constitutional Court (MK), Hamdan Zoelva, also commented. He said that when the constitution was amended to extend the term of office of the president, it was not impossible to add more in the future. This has great potential to destroy constitutional and national traditions.

“If it is opened again for one period, it is possible that it will be opened again for another period. This will be very bad in building the traditions of our state and nationality. Later it can be changed for the sake of temporary power," said Hamdan.

President Joko Widodo himself said that he had no intention of running for re-election. He is perpendicular to the constitution. However, the issue of constitutional amendments is emerging with various agendas, one of which is reviving the outlines of state policies or GBHN.

Will Indonesia extend the presidential term from a maximum of two to three? Usman Hamid, Executive Director of Amnesty International Indonesia said, “If the discourse of the three periods actually takes place, then the quality of the election is in jeopardy. This will end democracy after the New Order."