The room buzzed with applause from political science students at a campus on the outskirts of Jakarta. The applause was directed at the response to a question posed by one of the students, “Why isn't the candidate debate being held on campus? Even though we as students need more intense space to discuss with the candidates we will choose to lead this country?"

The response, which was also a hope for the 2019 Elections, seems will only be realized in the 2024 Elections, five years later. This is because there was a difference of opinion among election organizers at that time. Article 280, paragraph (1), letter h of Law No. 7/2017 on Elections prohibits campaigning in government facilities, places of worship, and educational institutions. However, in the explanation of this article, it is mentioned that government facilities, places of worship, and educational institutions can be used if election participants are present without campaign attributes and are invited by the responsible parties for those facilities.

This article creates legal uncertainty. As a result, even though the Election Law provides space for candidate debates to be held on campus, uncertainty makes parties on campus hesitant.

Students and the public must be satisfied with the official debates organized by the KPU, which have strict time constraints. Just imagine, we are "asked to be relieved" with answers to various issues within minutes. If you follow Twitter during the debate, there are lots of comments "Is that so?" and "Why is the answer so normative?" from multiple accounts. Leading for five years, but the explanation of the idea makes it even more confusing.

Campaign Regulation in Educational Institutions

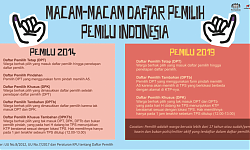

The restrictions on campaigning in educational institutions had been regulated in Article 74 letter g of Law No. 12 of 2003 concerning the General Election of Members of the People's Representative Council, Regional Representative Council and Regional People's Representative Council (UU 12/2003). However, exceptions are made with three conditions. First, on the initiative, or with permission from the head of the educational institution. Second, educational institutions provide equal opportunities to election participants. Third, activities do not interfere with the teaching and learning process.

These regulations are reiterated in Law No. 8 of 2012 concerning the Election of Members of the People's Representative Council (DPR), Regional Representative Council (DPD), and Regional People's Representative Council (DPRD). In the explanation of Article 86, paragraph (1), letter h of Law No. 8/2012, it is stated that educational institutions can be used if election participants are present without election campaign attributes, upon invitation from the responsible party for the educational institution. It is also clarified that educational institutions refer to the buildings and grounds of schools or higher education institutions.

The same norm is exactly stipulated in the explanation of Article 280, paragraph (1), letter h of Law No. 7/2017. Thus, the rules regarding campaign restrictions in educational institutions, along with the exemption norms, have been regulated since Law No. 12/2003. In Titi Anggraini's article titled "The Dilemma of Campaigning in Educational Institutions" (Media Indonesia, August 28, 2023), it is mentioned that campaign restrictions in educational institutions were not regulated during the 1999 elections.

Constitutional Court (MK) does not prohibit campaigns in educational institutions

The petitioner in case No. 65/PUU-XXI/2023 requested that the Constitutional Court (MK) prohibit campaigning in educational institutions, government facilities, and places of worship. However, in its decision, the MK only prohibited campaigning in places of worship.

In its legal considerations, the Constitutional Court (MK) explains that campaign restrictions in elections can be implemented by limiting the timing, media used, funding, as well as specific locations or places. Restrictions on campaigning based on location are based on several principles aimed at preserving the neutrality and integrity of the electoral process, preventing disruptions to public activities in specific places, and avoiding the misuse of public facilities.

"However, the principle of balance requires a balance between the rights and interests of candidates or political parties campaigning and the rights and interests of the general public and public institutions. Meanwhile, the principle of neutrality requires that certain public places remain neutral from practical political elements to ensure neutrality in the use of public resources. Based on these two principles, the prohibition or restriction of certain public places from being used for campaign activities is a necessity in conducting honest and fair elections," page 40 of Constitutional Court Decision No.65/PUU-XXI/2023.

In its decision, the Constitutional Court (MK) amended the campaign regulation in Article 280, paragraph (1), letter h to read as follows: "Using government facilities, places of worship, and educational institutions, except for government facilities and educational institutions, as long as they obtain permission from the responsible party for the facility and attend without election campaign attributes." This differs from the previous wording in the Explanation of the same article in Law No. 7/2017 on Elections, which stated: "Government facilities, places of worship, and educational institutions can be used if election participants are present without election campaign attributes upon invitation from the responsible party for the government facility, place of worship, and educational institution."

Thus, the Constitutional Court (MK) made two changes. First, it included the norm "as long as they obtain permission from the responsible party for the facility and attend without election campaign attributes" within the body of the article. Second, it changed the phrase from "upon invitation from the responsible party" to "as long as they obtain permission from the responsible party." This regulation of "obtaining permission" is similar to the wording in Law No. 12/2003.

Campuses can encourage substantive campaign debates.

The lively discussion about campaigning in educational institutions should be embraced by the academic community. Campus communities or groups can design party debates and candidate debates with selected issues or priorities as creatively as possible.

The choice of issues to address is limitless. It can range from worsening air pollution, climate change that could lead to food crises, environmental degradation, renewable energy, inclusive and marginalized-friendly participatory governance, reforms in various sectors, opportunities in technology utilization, economic diversification, to more inclusive open space issues and policies needed by youth.

Seizing public space for substantive issues doesn't even have to wait for campaign periods. Young people should not give in to narrative diversions that focus on trivial matters like identity politics based on ethnicity, religion, race, or even coalition name changes.

Campaigning in the form of candidate debates or party debates in educational institutions is not a problem, as long as it is fair and provides equal opportunities to all parties. The public needs many stages that can showcase and evaluate all those who could potentially hold government positions. We should not end up electing individuals who are far removed from what they have promised or offered. []

AMALIA SALABI

Translated by Catherine Natalia