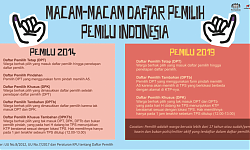

Indonesia is the most dynamic Southeast Asian country in changing the electoral system. Since the 1999 election, as the first election after the authoritarian era, until the 2019 Election, Indonesia has changed the electoral system at least three times. The 1999 election used a closed proportional system. The 2004 election with a semi-open proportional system. Election 2009 to 2019 with an open proportional system.

The three changes are only system variables for the voting method. On the other hand, the Indonesian election also changed system variables such as parliamentary thresholds, electoral districts magnitude, and the method of converting votes.

This dynamic does not occur in other Southeast Asian countries. In general, all countries still apply the electoral system that was abandoned by the country that carried out the previous colonization. Malaysia, for example, has continued to use the plurality system until now which was inherited by the British. The Philippines still uses a "mixed system" because it has long been a Spanish colony. Timor Leste, which is separated from Indonesia, uses a proportional system.

The issue of changing Indonesia's electoral system faces a new context at the 2024 election stage. A member of Partai Demokrasi Indonesia Perjuangan [the Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle] submitted a judicial review of the election law to the Constitutional Court. The article being tested is about an open proportional election system to be changed to closed proportional. If the Constitutional Court grants this, then the behavior of voting on ballots by selecting the name of the legislature candidate will change to selecting the image/name of a political party. In other words, the method of voting from the 2009 election to 2019 will change to the method of the 1999 election.

Hopefully the Constitutional Court will not issue a black and white decision. Because basically, the problem with the Indonesian electoral system is not a matter of maintaining open proportionality or returning to closed proportionality. Besides that, every electoral system has its drawbacks which need to include a solution of the consequences. It is important for the Constitutional Court and legislators to include comprehensive and systemic considerations so that the provisions made are not just a matter of open/closed.

Indonesia has a fundamental electoral system problem. First, the election resulted in an extreme multiparty parliament. Second, political parties with poor quality and have not been trusted by the public. These two fundamental problems are sustainable because 2022 is not used as a moment to improve the legal framework for elections and political parties. In fact, the 2019 Election was a very bad election systemically so that its complexity claimed hundreds of lives.

Extreme multiparty

Avoiding extreme multi-party formation in parliament does not guarantee that a country will be better off in democracy. However, no country that is good at democracy has an extreme multi-party party system. If we refer to a number of indices of countries in democracy/freedom (Freedom House) and clean from corruption (Transparency International), we can conclude that the ranking of countries between indices is relatively similar. If we relate it to the political system, it is found that none of these good countries have an extreme multi-party party system.

The Indonesia’s DPR party system, from the results of the 1999 election to the 2019 election, has seen an upward trend as an extreme multi-party. The definition of extreme multiparty here is that there are more than 5 relevant parties that can influence the government and the formation of laws. This calculation is based on the effective number of parliamentary parties (ENPP) formula. ENPP score 3 to 5, parliamentary party fragmentation is moderate. ENPP score more than 5, is extreme. Since Indonesia implemented a semi-open proportional electoral system in the 2004 DPR election with an electoral district size of 3-12 seats, the DPR has produced an extreme multi-party party system (7.1). Whereas in the 1999 election, a closed proportional system converted the votes of 48 political parties participating in the election to become moderate multi-party (4.7). Then in the 2009, 2014 and 2019 DPR elections with an open proportional system and a 3-10 seat electoral district, it still produced extreme multi-party (6.1, 8.2 and 7.5).

That is part of the reason, the loss of opposition in the DPR. The fluidity of party ideology in the DPR, because there are many parties whose percentage of seats is relatively even, so they work based on the goal of obtaining a share of power and development projects as a consequence of legislation. Deviations from policies and laws in the electoral field also occur in other fields. We can see how government-initiated legislation such as the Omnibus Law on Job Creation, the Revised Minerba (Mineral and Coal) Law, and the Law on the State Capital, which have many formal and material records, can quickly become legal without significant participation from the legislative, oversight and budget functions of the DPR.

We have mapped out that extreme multiparty makes bad governance in all countries. Changing the party system from extreme multi-party to moderate, can be done naturally and democratically. Among them by reducing the number of electoral districts from 3-10/3-12. If an open proportional system is chosen, the maximum number of seats will be 3. If a closed proportional system is chosen, the maximum number of seats will be 5. Too many seats per electoral district is a factor causing extreme multiparty formation in the DPR/DPRD. If there are too many seats in each electoral district, many political parties will set aside ideology in order to get lots of remaining seats. Too many candidates in an open proportional system are more likely to result in relatively balanced political party votes, resulting in an extreme multiparty system in the DPR.

So far, large electoral districts have encouraged political parties to only gain votes in various ways. Systemically, political costs have become very expensive. After gaining seats in the DPR, the parties set aside their legislative, oversight and budgetary functions. Being in power in the DPR means paying for political costs incurred in the previous election and then collecting them for the next election. Parliamentary politics is not only very expensive but also corrupt.

Poor Political Party

In addition to the extreme multiparty system, the poor quality of the Indonesian parliament is due to the poor quality of political parties. The results of the CSIS survey, which placed the DPR as the state institution most distrusted by the public, are linked to the results of the Political Indicator and Indonesian Survey Institute (LSI) survey, which ranked political parties as the most distrusted democratic institutions. The survey results in mid-2022 are fairly consistent with many similar survey results in previous years.

The public's poor evaluation of these political parties is in accordance with the level of entrenchment of political parties. Based on the results of a survey by Saiful Mujani Research and Consulting (SMRC) and Political Indicators, the score of party identification (Party-ID) in Indonesia continued to drop significantly from the 1999 election to the 2019 election. During the early post-Reform elections, around 86% of respondents said they were affiliated with a particular political party. This percentage fell by about half in the next election. Election 2004 at 55%. Election 2009 at 21%. The 2014 election was at number 11. Until the 2019 election, it was only at 7%.

The most systemic reason for keeping political parties away from the masses is the legal framework. Since the Reformation, the law on political parties has been revised four times. We can compare the changes from Law 2/1999, Law 31/2002, Law 2/2008, and Law 2/2011. From the initial revision in 2002 to 2011, the requirements for the formation of political parties became more stringent. Law No. 2/2011 has the most stringent requirements because political parties must have permanent management and offices in 100% of provinces, 75% of regencies/cities, and 50% of districts. This 100:75:50 condition is then applied as part of the requirements for political parties to participate in elections, including Law 7/2017 which is used in the 2024 Elections. Condition 100:75:50 has the consequence of requiring very expensive financial capital.

Political party reform must emphasize two things. First, which legal provisions must be changed in the Political Party Law and in the Election Law; second, through the authority of which state institution this change must be made.

There are at least two provisions that must be changed in the political party law and the elections law. First, facilitating the formation of political parties, for example returning the conditions in 1999. Second, changing the very difficult, complex and discriminatory verification of political parties participating in elections to only one requirement, namely transparent and accountable political party financial reports.

While changes to all of these provisions are sought in three forms of advocacy. First, continuing to provide political education and empowerment for citizens by collaborating with many parties such as NGOs, campuses, and certain political parties. Second, when the composition of MK Judges was relatively able to withstand the intervention of the DPR/President, conduct another judicial review of the provisions of the laws on political parties and elections by easing the requirements for the formation of political parties and the participation of political parties in elections. Third, these political party reform provisions continue to be conveyed to the current or next president to be followed up into a government regulation in lieu of law (Perpu) with the meaning of the urgency of compelling circumstances that two problems of the current electoral system have resulted in a state political emergency that is increasingly corrupt and increasingly undemocratic. []

USEP HASAN SADIKIN